By Steven D. Schmitt

Milwaukee Brewers fans will see more action-packed baseball in a more compact package in 2023 and beyond, making the game more enjoyable for all ages.

So says Brewers President of Business Operations Rick Schlesinger, who outlined the potential effect of a pitch clock, elimination of infield over-shifts, and larger bases on major league baseball in a speaking appearance February 28 at the Old Time Ballplayers of Wisconsin World Series Club dinner.

The pitch clock will require pitchers to deliver the ball to the plate within 15 seconds after receiving it from the catcher or umpire with the bases empty and 20 seconds with runners on base. Pitchers are penalized a ball for violations while batters lose a strike if they are not ready to hit. With the new shift rule, infielders must stay at their assigned positions, with the third baseman and shortstop to the left of second base, and the second baseman and first baseman to the right of second base, eliminating the three-on-one-side over-shifts that have frustrated major league hitters, particularly those that bat left-handed. “Rowdy Tellez is the happiest guy you’ve ever seen in spring training,” Schlesinger told the group of 40 Brewer baseball enthusiasts, cautioning that, “We won’t really know until the All-Star break what the overall effect will be.”

So says Brewers President of Business Operations Rick Schlesinger, who outlined the potential effect of a pitch clock, elimination of infield over-shifts, and larger bases on major league baseball in a speaking appearance February 28 at the Old Time Ballplayers of Wisconsin World Series Club dinner.

The pitch clock is expected to shorten games up to 28 minutes, based on experiments with the new rule in the minor leagues last season. The absence of infield shift will put more balls in play and presumably raise batting averages, Schlesinger said. Increasing the size of bases from 15 square inches to 18 square inches should increase stolen bases but enable faster force-outs and double plays. The shortening of games and the use of a ghost runner in extra innings, Schlesinger said, will please and attract more fans. “The game has to change and evolve with the fan base,” Schlesinger said. “The product has to appeal to a larger demographic. We are not reaching people under 40, 30, and 20 years old.”

As for watching the team on television, the Brewers sell broadcasting rights to sports networks as all major league teams do, but they also rank last in broadcast revenue. Schlesinger believes that issues with the current provider will be resolved but he expects major league baseball to someday administer television packages. He would like to explore the National Football League-style model to make smaller market teams more competitive. “The (current) system is not working for us,” Schlesinger said.

The Brewers also want to stay in Milwaukee by the time those people are 20 years older. Wisconsin Gov. Tony Evers has proposed a one-time cash investment of $290 million from the state’s $6.9 billion budget surplus to provide the Southeast Wisconsin Professional Baseball Park District – the Brewers’ landlord for American Family Field – with the resources for renovating the key components of the ballpark to make it competitive and sustainable through 2043. Those components include the retractable roof, the heating-ventilation-air conditioning units, seating, and scoreboard and technology improvements. A new audio system completed this year will ensure every fan hears announcements clearly regardless of seat location. Schlesinger is optimistic about the budget proposal that would meet the District’s obligations set forth in the stadium lease. “We’re looking to make sure our landlord has the money,” he said. Since the ballpark opened as Miller Park in 2001, it has generated $2.5 billion in state tax revenue and, in 2022 alone, created 3,000 jobs, according to the Metropolitan Milwaukee Association of Commerce. Brewer fans, however, won’t have to wait for an increase in food varieties and reduced concession prices, which will take effect this season. “You shouldn’t have to spend a week’s worth of salary to go to a Brewers game,” Schlesinger said.

And how competitive will the Brewers be this season? They have their core players and pitchers back but will have some new players that will add speed and excitement to the games, though some may not join the team until the season starts. “We have an excellent catcher who can hit,” Schlesinger said of the acquisition of William Contreras from the Oakland Athletics. “We need a little bit of luck, but we need to stay healthy more than anything else. “Schlesinger expects the St. Louis Cardinals and Brewers to battle for the N. L. Central and to renew a fan-pleasing rivalry with an improved Chicago Cubs team.

And how will the new rules affect Bob Uecker’s radio broadcasts? “He may have to make his stories a little shorter,” Schlesinger said.

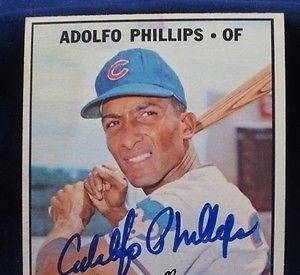

Another key player almost forgotten today was center fielder Adolfo Phillips, who became a folk hero when the Panamanian Flash hit four home runs, three in the second game, in a June 11 doubleheader sweep of the New York Mets at Wrigley Field. His dazzling catches in he outfield drew calls of “Olè!” from appreciative fans.

Another key player almost forgotten today was center fielder Adolfo Phillips, who became a folk hero when the Panamanian Flash hit four home runs, three in the second game, in a June 11 doubleheader sweep of the New York Mets at Wrigley Field. His dazzling catches in he outfield drew calls of “Olè!” from appreciative fans. Sadly, it was Culp’s 8th and final win of the season. It was Wait ‘Til Next Year once again.

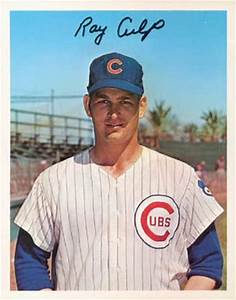

Sadly, it was Culp’s 8th and final win of the season. It was Wait ‘Til Next Year once again.

![[page image]](https://i0.wp.com/images.library.wisc.edu/UW/EFacs/UWClassAlbums/ClassAlbum1873/M/0098.jpg)