Willie Mueller is 58 years old, still lives in the Milwaukee area and loves to talk baseball. Maybe not about today’s baseball but his brief career in the Milwaukee Brewers’ and Montreal Expos’ organizations and how pitchers need to get batters out and get more work, pitching off a higher mound. “Hitters can hit speed,” Mueller said in a talk to the World Series Club of Milwaukee earlier this year. “Cutters and sliders get batters out.”

Mueller believes that baseball scouts today are always looking for hard throwers, meaning young fellows who can bring it 95 miles an hour. When they get called up from the minors, it’s a real eye-opener. “It’s a hard place to develop kids who have, or need, a breaking ball.”

Mueller knows of what he speaks, having signed a $15,000 contract (including incentive clauses) with the Brewers as a 17-year-old prospect on July 13, 1974. Mueller had graduated from West Bend West HS, the oldest of four kids, and signed the contract that scout Emil Belich had offered him. His rookie league manager was John Felske, who caught for the Brewers in 1972.

While in the minors, Mueller grew from a green kid 6′ 0″ and 180 pounds who threw 89 or 90 miles an hour to a 6′ 4″ 232-pound (he slimmed down to 220, according to Baseball Reference) Brewer pitching candidate who could throw 95. The road to the majors went through Newark (r NJ) in the New York-Pennsylvania League and both Clinton and Burlington, Iowa of the Class A Midwest League. His managers were Matt Galante and former Milwaukee Braves infielder Denis Menke. Mueller went 4-3 at the Class A level in 1976, then won 15 games for Menke’s Burlington Bees. His roommate, Paul Molitor, earned league MVP honors for the team that won the Midwest League pennant.

Willie Mueller as a Burlington Bee, 1977. Baseball Reference.

The jump from AA to the majors came in 1978, when Mueller went 7-5 with a 2.91 ERA at Holyoke (PA) of the Eastern League. He joined the Brewers in Boston on August 12 (with “no clothes, no toothbrush, no nothin'”) in the midst of a four-team pennant race that summer between the Red Sox, New York Yankees, Brewers, and Baltimore Orioles.

Mueller recalled that catcher Charlie Moore “made sure the glove would pop” in the bullpen. He entered a game in the fifth inning and worked 3 2/3 innings in relief of starter Mike Caldwell, a 22-game winner that season. Mueller struck out Butch Hobson looking, then gave up his first hit — a triple to Rick Burleson, who scored on second baseman Don Money’s error. Jim Rice flied out to end the inning. Mueller retired Carlton Fisk and Fred Lynn (on a line drive right into Mueller’s glove) and struck out Bob Bailey for his first 1-2-3 inning. He set the side cdown in order in the seventh, striking out Hobson looking for the second time. In the 8th, Jerry Remy singled with one out and Rice lined a home run over the green monster for two runs. “That’s the one that’s still travelin’,” Mueller joked. Fisk fouled out and Lynn, the AL Rookie of the Year and MVP, struck out to end Mueller’s major league debut.

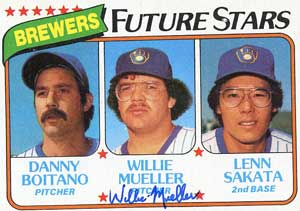

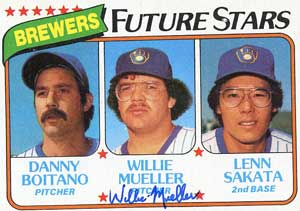

Mueller (center) was considered an excellent prospect. Topps.

On his lengthy stint, Mueller called himself “old school” and believes relief pitchers should pitch longer if they are getting hitters out, instead of being automatically removed for eighth-inning setup men and ninth-inning closers. He recalled that Rollie Fingers was “in the game to win the ballgame.”

Mueller pitched four more games and nine more innings for the Brewers that season and earned $21,000 (Baseball Almanac) and that was it. He toiled as a relief pitcher for the Vancouver AAA club of the Pacific Coast League over the next three seasons, working in 129 games. He pitched his last game for the Brewers on September 20, 1981, six weeks after the player strike ended, and allowed four hits and one run in two innings. He then joined the Montreal Expos’ top farm club at Denver and working one game before the end of the 1981 season. In 1982, Mueller worked 56 games for Montreal’s new AAA club, the Wichita Aeros — managed by former Brewer and Milwaukee Brave outfielder Felipe Alou — and returned to the Brewers organization in 1983. He never got back to the majors but worked 40 games out of the bullpen.

When Mueller’s major league career ended, it began, one might say, six years later. Not in the real major leagues but in the classic baseball movie Major League, starring Charlie Sheen of Two and a Half Men fame and Brewers Hall of Fame sportscaster Bob Uecker. The director asked Mueller to appear in the film after the auditioner asked if anyone knew someone “big and ugly who could throw the ball pretty hard.” Thus Mueller became the Duke, who lost the game in the bottom of the ninth inning. His teammates included Brewer pitcher Pete Vuckovich who played power-hitting first baseman Haywood and former major league and UW player Mike Hart.

Since his retirement from professional baseball, Mueller — whose top salary was $32,000 –has expressed disgust over the emphasis on home runs and offense and the attitudes and actions of today’s players. He has seen the mound shrink from 16 inches to 10, a strike zone that depends almost totally on the umpire, and the use of performance-enhancing drugs. Mueller said Ryan Braun’s denial in the biogenesis case “was the hard pill to swallow for the old Brewer guys.”

It is even harder to swallow the substance abuse, showboating and virtual absence of team cohesiveness. “There’s no meeting of the minds, there’s no backgammon, there’s no cards. Everybody is in it for themselves.”

Coach Willie Mueller of Concordia University. Mitch Holt.

That was not the way of the Bamberger-Rodgers-Kuenn Brewers that Mueller and the fan public fondly remember. Mueller ran laps with Jim “Gumby” Gantner and roomed with Hall of Famer Paul Molitor, now manager of the Minnesota Twins, who confided to Mueller, “I’m glad I got the job but I’m a little apprehensive. I know I can coach but I don’t know if I can be the guy who can lay the law down.”

Molitor need not fret. If he’s anything like his old-school roomie, he will find a way.

Mueller coached baseball for 17 years after his professional career ended, nine of those at Concordia University. Mueller still holds baseball clinics in the greater Milwaukee area.